I grew up in central Oklahoma. A small town, Crescent, Oklahoma. And my parents were both voting Republicans and I wasn’t aware there was an alternative. Everybody held those views. And I didn’t really understand them.

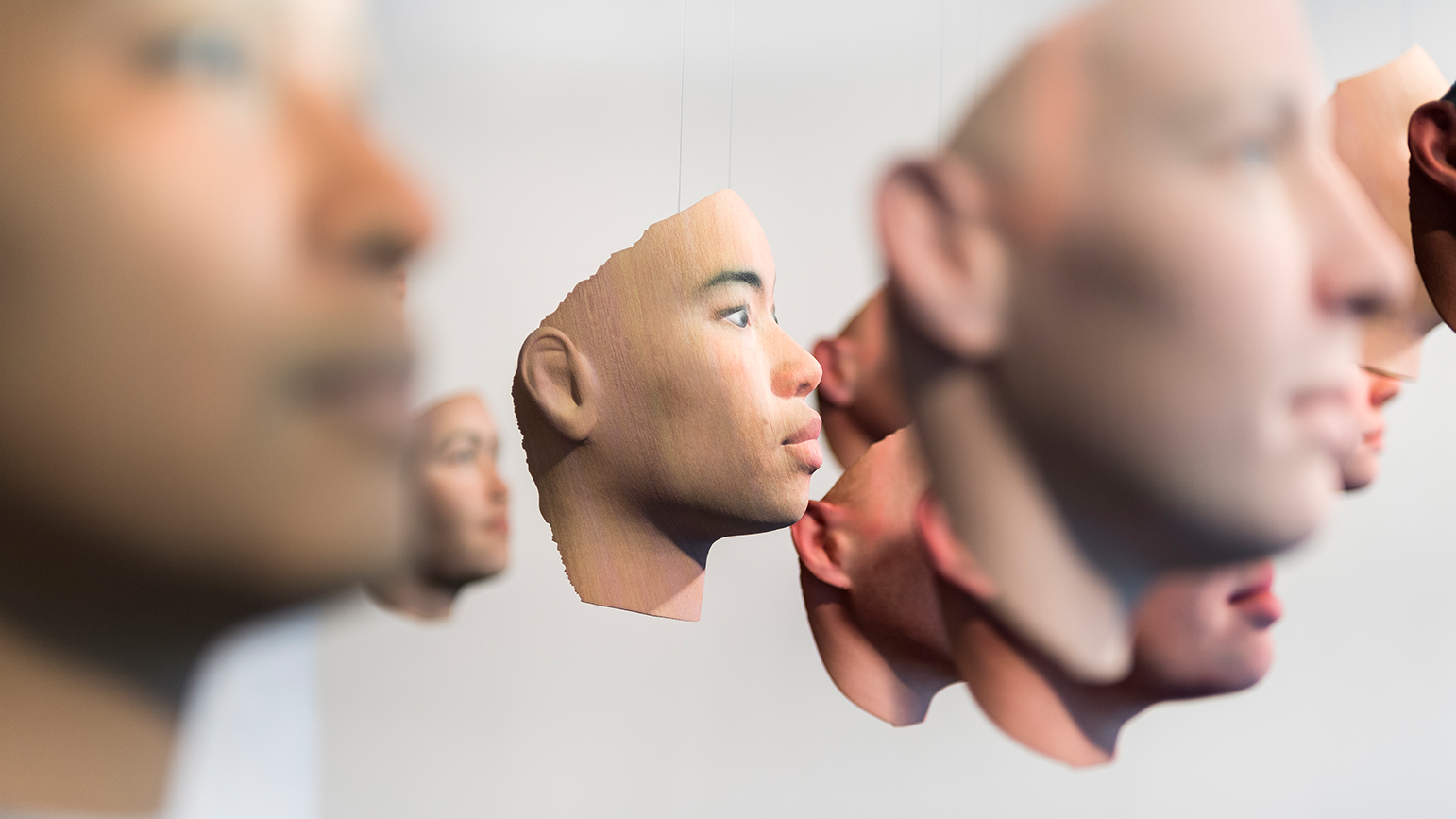

I’m trans and I felt different than everybody else. I knew I was different. I didn’t have words to like, describe that. All of my friends. All of my family. All of my teachers. They all knew it as well. It felt like there was something about me that was different. It caused friction. And it caused difficulty for me.

My mother is British, and when my mother and my father split up, my mother decided to move back to the UK, and so I went and I spent four years there. I went to school there, ya know, it was different. I was a kid from the mid west. I didn’t fit in. I didn’t know. It was just a completely different world for me.

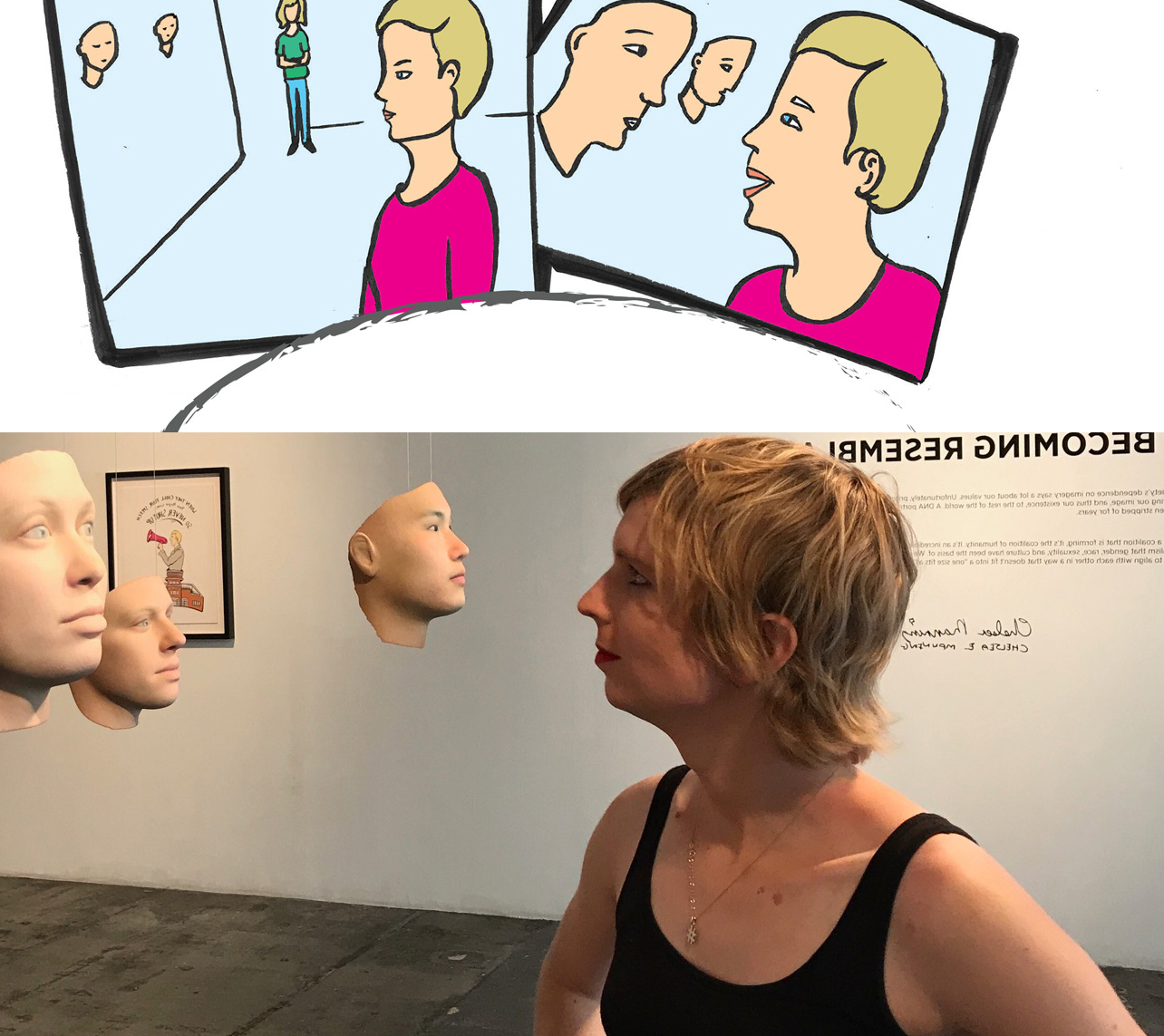

My father exposed me to computers at a young age. I learned how to program by the time I was about 8 or 9, although I didn’t fully understand probably till I was about 10. And my parents, we always had a computer in the house. And we always had internet access. So, it was a “normal” thing for me. Even though, at the time, in the early to mid 90s, it wasn’t a normal thing. And there were a lot of communities on the Internet in this time. And so, I was exploring. I was exploring who I was. I was exploring different ways of presenting myself.

I spent more time text messaging and instant messaging my friends than actually spending time with them. The term is IRL (In Real Life), but, ya know, we weren’t spending a whole lot of time IRL. My mother didn’t know how to write checks, so I used the internet to learn how. It ended up being a symbiotic relationship, but also my mother had a drinking problem, and as I got older, I realized how bad it was. And I love my mother. It just, I realized this is not the environment I needed to be in at the time. So I decided to move after my mom, she had a medical problem happen. And it was a scare for me, because I realized, if something happened to my mother, I didn’t have a back up plan. I didn’t have anywhere else to go.

So, I moved back. We didn’t get along. To say the least. I was 17, and I moved back to the states, and it was just very difficult because she (her father’s wife) didn’t like me, and so she was creating all these rules that were impossible to follow. Like, “you can’t leave your bedroom after 8pm.”

So she called the police on me one night, after an argument. It was over a sandwich, because I wanted to have a sandwich. It was 8:30 at night. So, I went out of the room, and I used *her* kitchen, after like 8 o’clock or whatever, to like make a sandwich. It was a swiss cheese and baloney sandwich. And I would cut it with a knife, so I had a knife in my hand. I wasn’t wielding it or anything like that. She had ran off and like, called the police on me. And I’m just like ok that’s weird. And so the Oklahoma Police Department knocked on the door. I’m like “hello,” and they’re like “we’re here for a domestic incident.” And I was like “Okay. She’s in there.” And so, like, the police officer understood what was going on. He basically said “you shouldn’t go back there.”

I borrowed my dad’s truck. I ended up driving to Chicago and living on the streets of Chicago for a summer in Chicago, and here I am living out of a pickup truck, and dealing with that.

My aunt did some detective work, and she asked around all the people that I used to hang out with. She told me that she called about 50 or 60 people, until she finally found somebody that had my cell phone number. So, I get a call from my aunt, and she’s like “come to my house,” and I did. I drove a night and a day, all the way to Maryland. And I lived with her for a year. It was so wonderful for her to be there for me at a time like this, and I realize now, that she really saved my life in many ways, and I didn’t realize it, I didn’t understand it at the time, cause I was so used to being in crisis mode that even whenever I was there, I was like “this is temporary.” So I was scared.

I was trying to re-establish a relationship with my father, and so I’m calling him, and he kept on saying “You need structure. You need the military. I was in the Navy for four years: You should go into the Navy or the Air Force.” And, at that time, the Iraq war was going on. So I saw the images on TV every day of chaos and violence in Bagdad, and I really wanted to do something. And I joined the Army because, ya know, it was Bagdad, where the fight was, and I wanted to help with that. I thought, “if I become an intelligence analyst, I can use my skills or learn something, and make a difference, and maybe stop this. — Chelsea E. Manning, October 8, 2017.